If You Walk Awy, I Will Follow

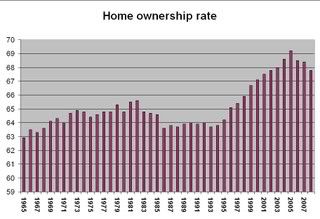

White has argued that the government should stop perpetuating default “scare stories” and, indeed, should encourage borrowers to default when it’s in their economic interest. This would correct a prevailing imbalance: homeowners operate under a “powerful moral constraint” while lenders are busily trying to maximize profits. More important, it might get the system unstuck. If lenders feared an avalanche of strategic defaults, they would have an incentive to renegotiate loan terms. In theory, this could produce a wave of loan modifications — the very goal the Treasury has been pursuing to end the crisis.

Precisely. Government officials have been urging people, Lowenstein recounts, to "do the right thing" and pay if they can afford to. In fact, underwater borrowers are parties to contracts that state the penalties for nonpayment, and if those penalties exceed the cost of continuing to make mortgage payments, not only do borrowers have the right to walk away, they arguably should walk away. By doing so, they are conveying the message that lenders overestimated what houses would be worth, and made loans to people who shouldn't have gotten them. Borrowers who walk away will pay costs, as they should, in the form of worse credit ratings. How much worse is up to lenders, who will have to decide if a walkaway is a bad credit risk. The sooner the information about the wisdom of past lending practices gets into the price system, the better.

Lowenstein notes that a Bush Administration official dismissed walkways as "speculators," which is true. All market traders -- people deciding whether or not to go to college, whether or not to take a particular job, whether to lend to someone to buy a house, whether to walk away from a loan to buy a house -- are speculating. They are using the information they have and the prices they face to make the best decision they can, thus injecting that information into the price. Given the pejorative meaning it has taken on, "speculation" is not even economically meaningful, and financial reporters should probably refrain from using it.

It is true also that a walkaway commits a negative externality by lowering property values on his street. But a person who moves into a neighborhood and makes a bid on a house also commits a positive externality, and in any event many of these externalities are properly internalized because a single person has built the subdivision to begin with. So that is not much of an argument either.

I suspect that most of the economic argument against walking away boils down to macroeconomics -- the fear that an epidemic of walkaways will cause the housing market to once again spiral down, delaying macroeconomic recovery. But this macroeconomic idea -- the idea that "the economy" is a single organism -- is bunk. What we ought to be concerned about is whether the microeconomics are right -- whether the price system is incorporating all the information it needs to to function properly. Given the contracts that were written, and the rules of the game for breaking them, underwater borrowers would be doing society a service by giving up homes that do not serve their interests.

Labels: Economics, Financial Crash