Better Late Than Never: Is Norman Angell Finally Right?

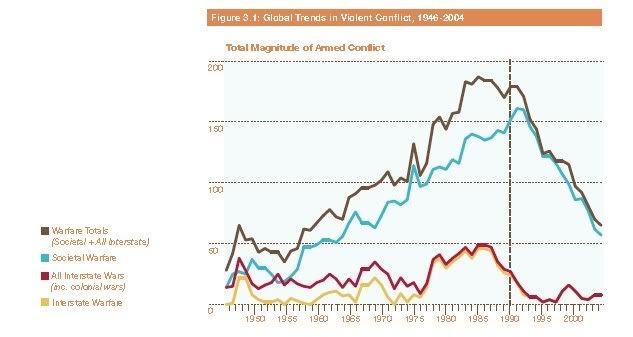

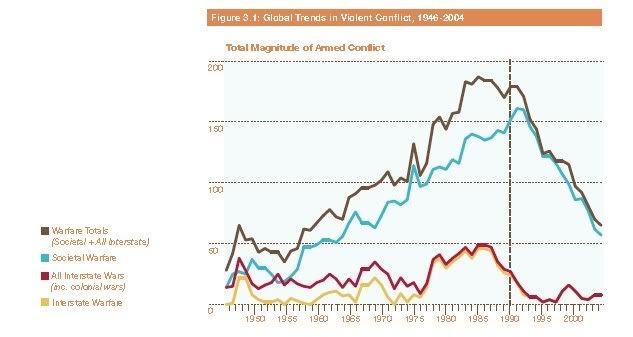

No one seems to have noticed it, but war - between states, between groups within the states, between anything in between - is on the decline worldwide. The down-and-dirty numbers are found courtesy of The Center for International Development and Conflict Management at the University of Maryland, in their Peace and Conflict 2005 report (pdf). Here is the key figure:

The cresting of war of all sorts just before the breakup of the USSR has passed, I must say, with surprisingly little comment. One might suppose we are standing on the threshold of one of the greatest human achievements of all time, on a par with the adoption of agriculture or the Industrial Revolution - the obsolescence of war as a means of dispute settlement in all but the remotest (from civilization) regions of the world. But there has been almost none from officials in the UN or major world governments, who might be expected to crow at this development.

As a matter of "if it bleeds, it leads" this is understandable. One major war is the war in Iraq, where the world's mightiest military power is mired in a seemingly mindless conflict where car bombs against innocent civilians and death-squad beheadings are the primary means of waging war. Mix in the fact that the U.S. military, with all of its PR officers, its embedded journalists, and the predisposition of journalists to seek out its failings, cries out for opportunistic coverage, and mix in too the spectacularly telegenic carnage of September 11, and it is no wonder that very intelligent people feel that the world is in the midst of an epoch, world-historical struggle. (I visit the sites of some of these thinkers regularly - this one is perhaps my favorite.)

But the numbers, clearly, say otherwise. Why is war on the way out? Norman Angell, whose name is in the title of this piece, had the misfortune to claim, in The Great Illusion, that economic interdependence among nations was making war obsolete. (That trade deters interstate war is a proposition supported in the research, and that it deters tribal conflict within nations is a favorite theme of this blog.) Alas, he had the misfortune to write it in 1911, a mere three years before the attempted suicide of Western civilization after Sarajevo.

But there is surely something to the idea that we depend on one another so much that it is more productive to bargain and trade than to try to settle disputes forcibly, the more so given the spectacular destructiveness of today's weapons. Others might attribute the epidemic of peace to the rise of the collective-security system through the UN, or the creation of organizations like the IMF and the WTO that give nations venues to jaw, jaw, jaw, as Churchill is said to have put it, instead of war, war, war.

A political scientist at Ohio State named John Mueller has what may be the most provocative thesis - that war has simply become morally unacceptable to most of humanity because of its costs, and so has become shamed into its darkest corners, much as slavery was gradually over the previous several centuries. (Slavery still goes on, of course, but it is seen as a disgrace; even nations that practice it pretend they don't.) Indeed, he amplifies the thesis in a self-evident (from the title) way in his latest work, Overblown: How Politicians and the Terrorism Industry Inflate National-Security Threats, and Why We Believe Them.

If these people are right, we are at potentially a critical, even epochal moment (if we seize it) in human history - a moment when global opinion can relegate warmaking to the dustbin of our disreputable past. It is a provocative thesis, which we ignore at our peril. But there are other historical regularities worth noting, notably the rise of China combined with the tendency of such newly minted powers (Germany in the 1870s, the U.S. from 1845-1898, Japan from 1905-1941) to throw their weight around aggressively in their own neighborhood, and the unchallenged military dominance (in an interstate sense) of the U.S., which provides temptations to see military force as the hammer before which all its international disputes become nails. Despite its immense promise, given the power of modern weaponry the thesis would only have to be wrong once for disaster to happen.

The cresting of war of all sorts just before the breakup of the USSR has passed, I must say, with surprisingly little comment. One might suppose we are standing on the threshold of one of the greatest human achievements of all time, on a par with the adoption of agriculture or the Industrial Revolution - the obsolescence of war as a means of dispute settlement in all but the remotest (from civilization) regions of the world. But there has been almost none from officials in the UN or major world governments, who might be expected to crow at this development.

As a matter of "if it bleeds, it leads" this is understandable. One major war is the war in Iraq, where the world's mightiest military power is mired in a seemingly mindless conflict where car bombs against innocent civilians and death-squad beheadings are the primary means of waging war. Mix in the fact that the U.S. military, with all of its PR officers, its embedded journalists, and the predisposition of journalists to seek out its failings, cries out for opportunistic coverage, and mix in too the spectacularly telegenic carnage of September 11, and it is no wonder that very intelligent people feel that the world is in the midst of an epoch, world-historical struggle. (I visit the sites of some of these thinkers regularly - this one is perhaps my favorite.)

But the numbers, clearly, say otherwise. Why is war on the way out? Norman Angell, whose name is in the title of this piece, had the misfortune to claim, in The Great Illusion, that economic interdependence among nations was making war obsolete. (That trade deters interstate war is a proposition supported in the research, and that it deters tribal conflict within nations is a favorite theme of this blog.) Alas, he had the misfortune to write it in 1911, a mere three years before the attempted suicide of Western civilization after Sarajevo.

But there is surely something to the idea that we depend on one another so much that it is more productive to bargain and trade than to try to settle disputes forcibly, the more so given the spectacular destructiveness of today's weapons. Others might attribute the epidemic of peace to the rise of the collective-security system through the UN, or the creation of organizations like the IMF and the WTO that give nations venues to jaw, jaw, jaw, as Churchill is said to have put it, instead of war, war, war.

A political scientist at Ohio State named John Mueller has what may be the most provocative thesis - that war has simply become morally unacceptable to most of humanity because of its costs, and so has become shamed into its darkest corners, much as slavery was gradually over the previous several centuries. (Slavery still goes on, of course, but it is seen as a disgrace; even nations that practice it pretend they don't.) Indeed, he amplifies the thesis in a self-evident (from the title) way in his latest work, Overblown: How Politicians and the Terrorism Industry Inflate National-Security Threats, and Why We Believe Them.

If these people are right, we are at potentially a critical, even epochal moment (if we seize it) in human history - a moment when global opinion can relegate warmaking to the dustbin of our disreputable past. It is a provocative thesis, which we ignore at our peril. But there are other historical regularities worth noting, notably the rise of China combined with the tendency of such newly minted powers (Germany in the 1870s, the U.S. from 1845-1898, Japan from 1905-1941) to throw their weight around aggressively in their own neighborhood, and the unchallenged military dominance (in an interstate sense) of the U.S., which provides temptations to see military force as the hammer before which all its international disputes become nails. Despite its immense promise, given the power of modern weaponry the thesis would only have to be wrong once for disaster to happen.

4 Comments:

This comment has been removed by the author.

This comment has been removed by the author.

I wouldn't declare Norman Angell vindicated quite yet. We still have plenty of Islamic jihadists to contend with. In their minds, I don't see how petty little concerns like interstate trade and interdependence are going to compete with the demand for global Islamic dominion and the promise of a ticket to eternal Paradise for anyone who fights to bring that dominion about.

There are certainly many (in absolute, not necessarily relative terms) Muslims who want to see us all dead. As we saw on 9/11, they only have to get lucky once.

But globally, and historically, the jihad may be a minor episode; it remains to be seen. The only thing that makes it truly frightening is the possibility that jihadis get the bomb. The extent to which we should reorient our open societies in the face of this threat of unknown size is the key question of our time.

Post a Comment

<< Home